Thanks to a landmark piece of legislation that’s been in the works for years, public lands in the United States from the biggest national parks to the smallest ballfields and fishing lakes are about to get a massive infusion of funding that conservationists say is long overdue.

On Wednesday, Congress passed the Great American Outdoors Act, which combined two earlier bills to commit $900 million a year to the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) and $9.5 billion over five years to address critical infrastructure updates across the National Park Service, Forest Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Land Management.

“Passing the Great American Outdoors Act is quite simply the most significant investment in conservation in decades,” said president and CEO of the National Wildlife Federation Collin O’Mara in a statement.

“It’s a huge win for wildlife, our natural treasures, our economy, and all Americans, who enjoy our America’s public lands for solace, recreation, and exercise, especially amid this pandemic. All Americans will benefit from this historic legislation, which will create hundreds of thousands of jobs, expand outdoor recreation opportunities in every community, and accelerate our nation’s economic recovery from COVID-19.”

Rafting tours down the Snake River near Grand Tenton Mountains ©Mark Read/Lonely Planet

Rafting tours down the Snake River near Grand Tenton Mountains ©Mark Read/Lonely Planet

The expansion of access to outdoor spaces, and the restoration of existing destinations is crucial as more and more Americans have turned to outdoor recreation in recent years. Some 327 million travelers a year visit national parks, forests, and Wild and Scenic Rivers from Mt. Rainier and the Rouge River to the Great Smokey Mountains and the New River Gorge, traveling over some 5000 miles of paved roads, nearly 20,000 miles of trails, and making use of almost 25,000 buildings.

Back in June, when the US Senate initially passed the Great American Outdoors Act, the Land Trust Alliance noted that the LWCF has “only been fully funded once in its history,” despite the fact it’s been promised $900 million a year since its inception and supports “over 41,000 state and local park projects, contributing $778 billion to the nation’s economy annually and providing 5.2 million sustainable jobs nationwide.”

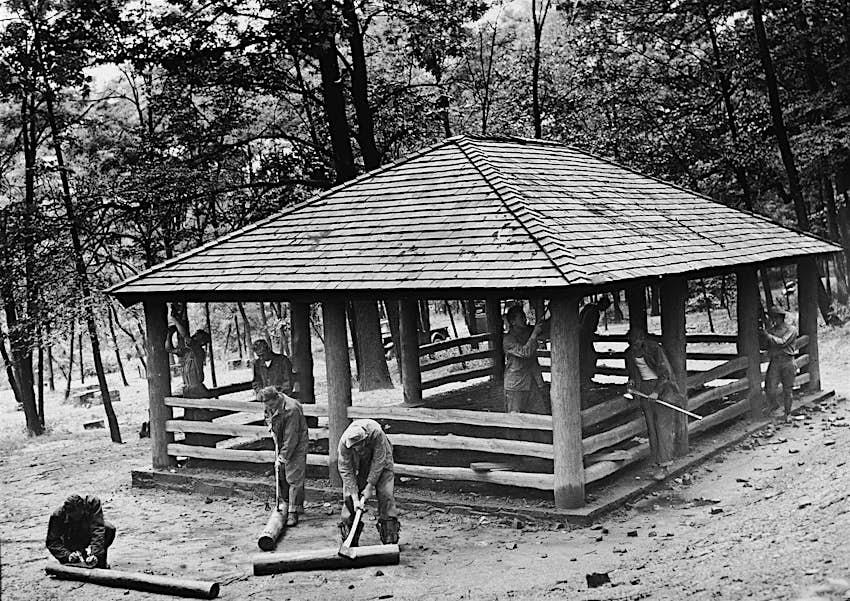

Men from the Civilian Conservation Corps finish a shelter house at South Mountain Reservation, New Jersey, 1935. Many such structures are still in use today. © New York Times Co. / Getty Images

Men from the Civilian Conservation Corps finish a shelter house at South Mountain Reservation, New Jersey, 1935. Many such structures are still in use today. © New York Times Co. / Getty Images

Because budgets haven’t increased even as traffic on public lands has grown, officials haven’t been able to keep up with the deterioration of key infrastructure nearing, or past, the end of its lifespan. A significant portion of the federal assets at national forest campgrounds, national parks, and state parks were built nearly a century ago, when the Civilian Conservation Corps was put to work during the Great Depression. According to the Pew Charitable Trust, 70% of the National Park Services’ overdue projects pertain to structures at least 60 years old.

That’s had big, costly consequences that impact visitor experiences. For example, a sink hole nearly the length of a subcompact car opened up in Shenandoah National Park on the busy George Washington Memorial Parkway last May – and it wasn’t the first such incident in the park. The series of sinkholes were the result of delays to roadwork and updates to storm water drainage networks, the kind of problems that are cheaper to fix before they eat into an entire roadway.

Hunt’s Mesa at sunrise, Monument Valley, Arizona, Utah, USA ©Francesco Riccardo Iacomino/500

Hunt’s Mesa at sunrise, Monument Valley, Arizona, Utah, USA ©Francesco Riccardo Iacomino/500

Meanwhile, the Transcanyon Pipeline in the Grand Canyon is fifty years old and perpetually leaky. Built in the 1960s in the midst of Mission 66, one of the last major flurries of upgrades to the national parks system that formed in response to similar concerns about degraded infrastructure and funding, the pipeline has been a focus for replacement for years. Although the pipeline supplies all the potable water to the South Rim of the park, officials have carried on with makeshift repairs because they haven’t had the $100 million necessary to build an alternative.

“LWCF is an issue I’ve been working on since my introduction into the outdoor policy world six years ago,” said Katie Boué, founder of the Outdoor Advocacy Project. “This week’s passage marks a huge victory for so many advocates who have invested years in making it happen. In a time when our public lands and green spaces are more valued and visited than ever before, it gives me hope to see Congress stepping up to support them.”

High-angle view of Jackson city covered in snow and the Teton Valley. ©Adventure_Photo/Getty Images

High-angle view of Jackson city covered in snow and the Teton Valley. ©Adventure_Photo/Getty Images

Budget constraints have also made it harder to establish new public lands and expand existing parcels, especially around fragile conservation areas like the Everglades and the Grand Tetons that are experiencing increased development nearby. In January environmentalists celebrated when the state of Florida purchased 20,000 acres of swampland that feeds the Everglades in order to end Kanter Real Estate’s multi-year quest to drill oil on the parcel. A greater number of similar deals will be possible at the federal level now the Great American Outdoors Act has secured permanent funding.

It’s been proven that new national parks can be a big hit, like when visitor numbers soared at Indiana Dunes after it was designated a national park in January of 2019. The same was true for White Sands National Park in New Mexico – the newest of the country’s 62 national parks. The increase in funding could aid efforts to upgrade a handful of national forests and monuments that advocates hope could be national parks candidates, like Craters of the Moon in Idaho and Louisiana’s Atchafalaya National Heritage Area, without further stretching a cash-strapped National Parks Service.

White Sands National Park Yucca picnic area covered in sand in New Mexico. ©krblokhin/Getty Images

White Sands National Park Yucca picnic area covered in sand in New Mexico. ©krblokhin/Getty Images

Exactly where and how to first apply the funds secured by the Great American Outdoors Act still needs to be decided by multiple federal agencies. But legislature’s passage is reason enough for outdoor enthusiasts and activists to celebrate – it heralds the biggest overhaul the parks have received in a generation. And with many grounded travelers turning to road trips and visits to state and national parks in lieu of international travel as a result of the global coronavirus outbreak, the timing couldn’t be better for the country’s beleaguered public lands.

“As an avid outdoors woman and activist, I’ve been going to DC for many years advocating for more funding for our national parks, public lands and green spaces,” said Caroline Gleich, an Utah-based environmental advocate and pro ski mountaineer who summited Mt. Everest last year. “As America is dealing with the pandemic, more and more of us are turning to our parks and public lands for our mental and physical well being. The passage of the Great American Outdoors Act gives us something to celebrate. It gives us hope for the future.”