The Second World War and Holocaust Galleries will explore themes of persecution, escalation, the development of violence toward Jewish people, and the rise in tensions that followed World War I.

A V1 “doodlebug” bomb will occupy a space between the new Second World War and Holocaust Galleries.

Imperial War Museum

“The Holocaust looms large in contemporary culture but the version of it that looms large isn’t necessarily the historic occurrence that was the Holocaust, it’s a kind-of constructed, cultural re-imagining of it,” historian James Bulgin, in charge of the new Holocaust Galleries’ content, told CNN.

“That’s built around certain, very centralized tropes, like deportation trains, selections at Auschwitz and gas chambers. Obviously all of those things are really important, but the Holocaust is a much bigger, much messier, complex history than that,” he said.

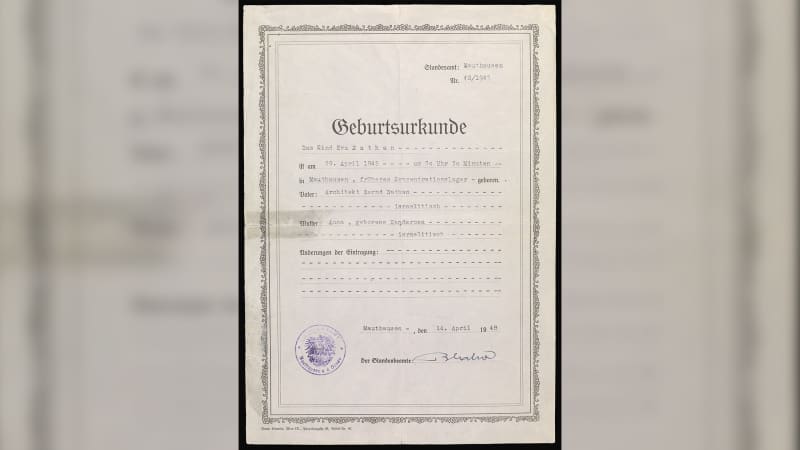

The birth certificate of Eva Clarke, who was born in the Mauthausen concentration camp, will be on show.

Imperial War Museum

The museum has said the Holocaust Galleries, due to open in October, will examine the “ordinary” identity of the perpetrators, explaining who was responsible for these crimes, exploring their motivations and showing how seemingly normal they were in everyday life.

They will feature personal stories of both perpetrators and victims, alongside objects, documents and photographs aimed at helping visitors understand the cause, course and devastating consequences of the genocide.

Among the objects to be featured in the gallery will be the birth certificate of Eva Clarke, one of just three babies born in Mauthausen concentration camp who survived past liberation.

The galleries will be airy and well-lit, Bulgin said, to remind visitors that the atrocities happened “in our world.”

“Allowing the Holocaust to become this apotheosis of industrialized genocide removes so much of the human dimension to it — for experiencing it, but also those doing it,” he said.

“In some people’s imagination the process of genocide that the Holocaust represents was almost something that developed an unstoppable momentum, and it meant that the people who were doing the killing and the people who died were just part of an industrialized process,” he said, adding that such an interpretation suggests that those who participated in the atrocities had no agency.

“But the reason the Holocaust developed as it did was because people — individuals — continued to make decisions day after day, week after week, month after month, even year after year,” he added.