The global increase in demand for protein has been a boon for tree nuts generally and almonds specifically. As a result, the almond industry is growing rapidly not only in the United States, but also in countries such as China and India. As more people in these countries enter the middle class, the demand for almonds as a source of protein and nutrition will only get stronger.

Nearly 80% of the worlds almonds grow in California with the remaining share growing in Australia, China, the EU and Turkey. Despite almonds being a critical part of California’s overall agricultural economy, growing concerns over drought in the Western United States has resulted in a lot of negative publicity for this increasingly popular tree nut. Headlines such as “It Takes a Gallon of Water to Grow an Almond” are growing in popularity especially as the drought worsens.

At Terra Ag, we’re bullish on the almond market and long on this commodity. As such, I thought it would be useful to give an overview of the lifecycle of an almond to help inform readers on what is involved to grow and sell this tree nut to the masses. I also want to bust some of the more outrageous myths around water usage as it pertains to almonds.

The Beginning

Yes, almonds do grow on trees. The San Joaquin Valley is the most abundant production area for almonds globally. If you are driving down the I-5 from San Francisco to Los Angeles, you’ll notice rows of neatly planted trees going on for hundreds of miles. These trees are most likely almond trees some of which may have been planted 20-25 years ago.

An almond tree does not produce almonds immediately. Rather, it takes about 3-4 years after an almond tree is planted for a commercially viable almond crop to take. From there, the almond tree will typically grow more productive until it peaks in production capacity around year 7 or 8. It will then continue to produce a commercially viable crop for another 12-15 years when yields will start to decline. At this point, a critical decision will need to be made by the farmer – should I pull out the trees and replant or should I continue to farm the trees as is to save costs.

Newly Planted Almond Tree

Terra Ag

Water and Irrigation

Because rain alone in California is not sufficient to grow a commercially viable almond crop, farmers need to supplement the rain with irrigation. Historically, the most common irrigation method was flood irrigation where a farmer would flood her field and submerge all of the trees in water. This allowed the farmer to save on expensive infrastructure costs such as underground pipes and micro-irrigation technology and made sense when water was abundant and cheap.

However, as water has become more scarce and farmers have become more aware of their own impact on the environment, flood irrigation is a rare occurrence. Rather, most almond farmers use highly efficient irrigation methods such as drip irrigation or micro-sprinkler irrigation. Unlike flood which has 50% efficiency, these new irrigation methods have efficiencies as high as 95%. What this means is that we can now grow a pound of almonds with a lot less water than we did 10-20 years ago.

Additionally, some farmers are taking it a step further by using subsurface drip or Deep Root Irrigation. These methods are even more efficient in that they reduce or eliminate the evaporation of water that occurs when the irrigation is applied at the soil surface. Rather, the water is applied directly to the roots of the tree below the soil surface. With growing concerns over drought, water and climate change, subsurface irrigation will become more popular in California. At Terra Ag, we have already converted many of our existing orchards to this technology in order to save water and increase efficiency.

Micro-irrigation being applied to mature Almond Trees

California Almond Board

Irrigation Districts and Groundwater

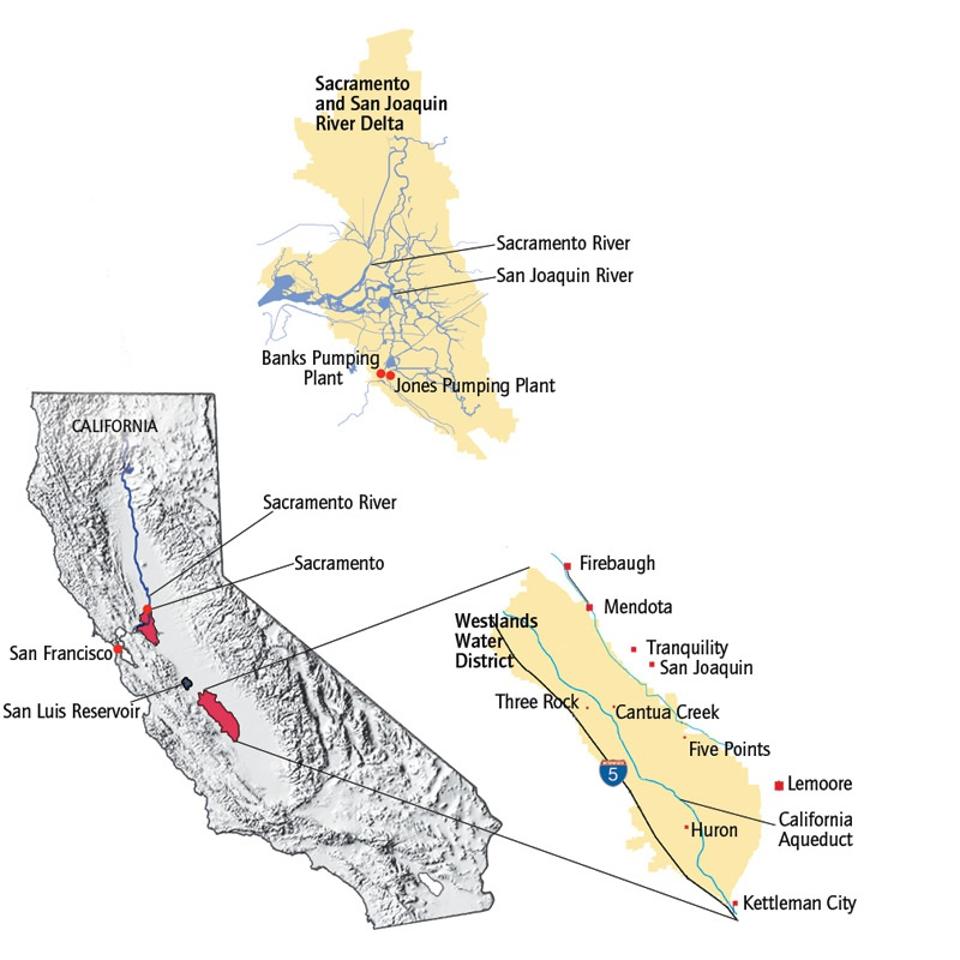

Because water is such an important part of almond farming in California, it is important then that there be some level of governance when it comes to water availability and allocation. Accordingly, California has dozens of irrigation districts throughout the state in charge of making water available to farmers within their jurisdiction and ensuring that this critical resource is not wasted.

But not all irrigation districts are created equal. Rather, in California, there are the haves and the have nots. In some cases, irrigation districts have such strong water rights (what they call pre-1914 water rights) that even in the worst water years (such as 2015 and 2021) water availability is abundant and relatively inexpensive. On the other hand, there are irrigation districts that are dependent on federal or state water where in a year like this year, the irrigation district has 0% allocation and a farmer must rely on her wells (assuming she has wells) to irrigate her crop.

It is no surprise then, that water availability dictates the viability and value of a piece of property in California. And the problem is only worsening with the passage, in 2015, of the Sustainability Groundwater Management Act or SGMA for short. Historically, groundwater pumping in California has been governed by the doctrine of reasonable use. As long as you are pumping water and not wasting it, you can pump as much as you want. The consequence of this decades old precedent has been declining aquifer levels throughout the state especially in drought years.

Water Districts in California

High Country News

Understanding this, Governor Jerry Brown passed SGMA as a way to preserve our aquifer levels (some of which have taken tens of thousands of years to take shape). Accordingly, by the year 2040, every aquifer and basin in California must be net neutral in terms of how much water is being taken out versus being put back into the ground. Think of it like a bank account. Your bank balance can go up and down over time but if it goes below zero, then you are assessed fees and penalties. SGMA works in a similar fashion.

Cultivation

The almond season starts in late October after the prior years harvest. During this time, it is critical to give the almond trees enough nutrition before dormancy that they are ready to push buds during bloom time in February. This mainly entails applying nitrogen, potassium, zinc and phosphate to the trees. These nutrients can be applied through the irrigation water (often called fertigation), spread onto the soil in a dry format or applied in a foliar spray to the leaves of the tree.

Around December, the trees will lose all their leaves and go dormant (i.e. fall asleep). During this time, the trees will not uptake any nutrition or water. They will come out of dormancy in late January and that is also when they are ready to go through “bloom”. Bloom is when the almond trees start pushing buds and eventually flowers that need to be pollinated by honey bees in order for the buds to eventually produce almonds.

Bloom time is why California is the only place in the United States where almonds are viable. It is critical during this time that the air temperature not approach freezing otherwise it will kill the buds and drastically impact the crop. California’s mild winters is why almonds are so successful in this state as compared to other western states such as Arizona or New Mexico.

Almond Bloom in California in February

Terra Ag

Once the flowers are pollinated, the trees will start producing foliage (leaves) and small nuts that will eventually become the almonds we consume. This usually occurs around early March. This is also the time when irrigation water and additional nutrition is applied to the tree in order to size the almond kernels and ensure they remain on the tree rather than fall off before fully maturing. Again, this means applying nitrogen, potassium, phosphate and micronutrients such as zinc, boron and iron either through the water, in a dry format to the soil and/or to the leaves in the form of a foliar spray.

The water usage also increases gradually from March through July, peaking in July and then declining from July through October. From March through July, the almond kernels are increasing in size. As a result, nutrition and water is critical during this time to ensure there is sufficient energy to properly size and sustain the crop. Many farmers may also employ what is called “deficit irrigation” especially in years like this year. Deficit irrigation is a way to reduce the water needs of the tree without necessarily impacting the crop. Deficit irrigation is mainly applied after the almond kernels have fully sized (in July) and can lead to 20% savings in water requirements during that time.

In addition to nutrient requirements, almond trees also require fungicides and insecticides to protect the crop from disease and insects. The main fungal sprays are applied during bloom time in February. Insecticides, on the other hand, are mainly applied in the summer to protect the crop from mites and naval orange worm or NOW for short.

Harvest

Almond harvest in most parts of the state begins in early August. Although historically almond harvest may have been a labor intensive manual process, today, almonds are mostly mechanically harvested through tree shakers, sweepers and harvesters.

Harvest starts when a tree shaker shakes each tree in order for the nuts to go from the tree to the ground. It is critical to time this properly. You don’t want to shake too early otherwise not all the nuts will come off the tree or you will have nuts that are not yet ready or have too much moisture. You also don’t want to shake too late otherwise you will increase your insect damage and stress on the tree.

Almond Shaker

Rear End Shop

Once the trees are shaken, the almonds are swept into neat rows using a sweeper. From there, they are picked up from the ground with a harvester and trucked over to a huller. Almond kernels, while on the tree, grow inside a woody shell and are enclosed within a greenish brown hull. Neither the shell or the hull are edible. Rather, the almonds we purchase and eat as consumers are the edible almond kernel. Accordingly, the huller will remove the hull (and sometimes the shell) leaving only the edible kernel. The kernels (and in some cases the kernels within the shell) are then sold to various processors around the state that then package or further process them and then ultimately sell the almonds domestically and abroad to the end wholesaler or retailer. The largest processor in the state of California is Blue Diamond. The hull doesn’t go to waste, though, and is often sold to dairies as cow feed given its high nutrient content.

Almonds Swept Into Neat Rows

Produce Nerd

Once the almonds are sold to the processor, the processor may then turn them into products such as nut butters and almond milk or sell them as is so they can be consumed as whole almond kernels. Over the last decade, China has been the largest importer of California Almonds. However, with the tariff wars and the higher duty on almonds, more recently India has overtaken China as the largest importer of California Almonds. Despite the global demand for almonds, the United States is still the largest consumer of almonds globally.

Almond Kernels In Shell

Terra Ag

Replanting Considerations

At the end of an almond tree’s economic life (typically when the trees are between 20-25 years old), an almond grower is left with an important question: should I pull out the trees and plant a new orchard? This consideration often involves weighing different data points including current production levels at the orchard, the state of the almond market, and replant costs and availability of cost effective capital.

If the grower does decide to replant her orchard, then the process described above starts all over again. Replanting an orchard begins with the grower pulling out the existing trees and then preparing the land for by deep ripping the soil to loosen it and remove any hard pan, disking and floating the ground, installing the irrigation infrastructure and finally planting new trees. Oftentimes, the almond varieties that were popular 20-25 years ago (when the orchard was first planted) may have been superseded by newer more popular varieties. Another consideration for the grower when deciding to replant.

Grinding Old Almond Trees to Produce Green Compost

Pacific Nut Producer Magazine

Replanting is another opportunity for growers to utilize sustainable practices. For example, an increasingly popular practice in California includes pulling out the trees, shredding them and then applying the green compost back to the soil before planting the new trees. At Terra Ag, we’ve done this on many of our replant orchards. By doing this, we not only eliminate the need to burn the old material, but also eliminate transportation costs to haul the material away and increase the microbial content of the soil. This in turn, allows the soil to capture more carbon which may also be a potential solution for climate change.

Looking Ahead

Looking ahead, almond cultivation has suffered from drought and almond prices have suffered from record production in 2020 and the US/China Tariffs. Additionally, as almonds are a snacking product heavily used in the hospitality and travel industries, prices have also experienced headwinds due to Covid-19. However, continuous demand has kept pricing stable albeit below historical averages. And with the USDA objective estimate for the 2021 almond crop coming in well below projections, almond prices have started to recover.

As you can see from the above described process, farming and producing almonds is not easy. And the process is only getting tougher with labor shortages, multi-year drought and increasing regulation. However, most almond farmers I have met and talked to are resilient. They love what they do and are committed to preserving natural resources and using regenerative practices that are good for their farm and the environment. Accordingly, next time you go to your local farmers market or grocery store and you come across a bag of almonds or almond milk or almond butter, remember everything that went into making that product available to you.