Cows have a special “superpower.” They can digest cellulose – the most abundant form of plant-captured solar energy on the planet. This means they can live by grazing on grasses and in doing so they enable human food production on hundreds of millions of acres of rangeland and pastureland that is unsuitable for crop production. According to one source, grazing lands occupy 26% of all global land area while cropland only covers 12% (Source). Cattle can also be raised on hay and various other cellulose-rich forages. They can eat crop side-streams like straw and even almond hulls. For humans, the cellulose we consume in fruits, vegetables and cereals is just “dietary fiber,” not a source of energy.

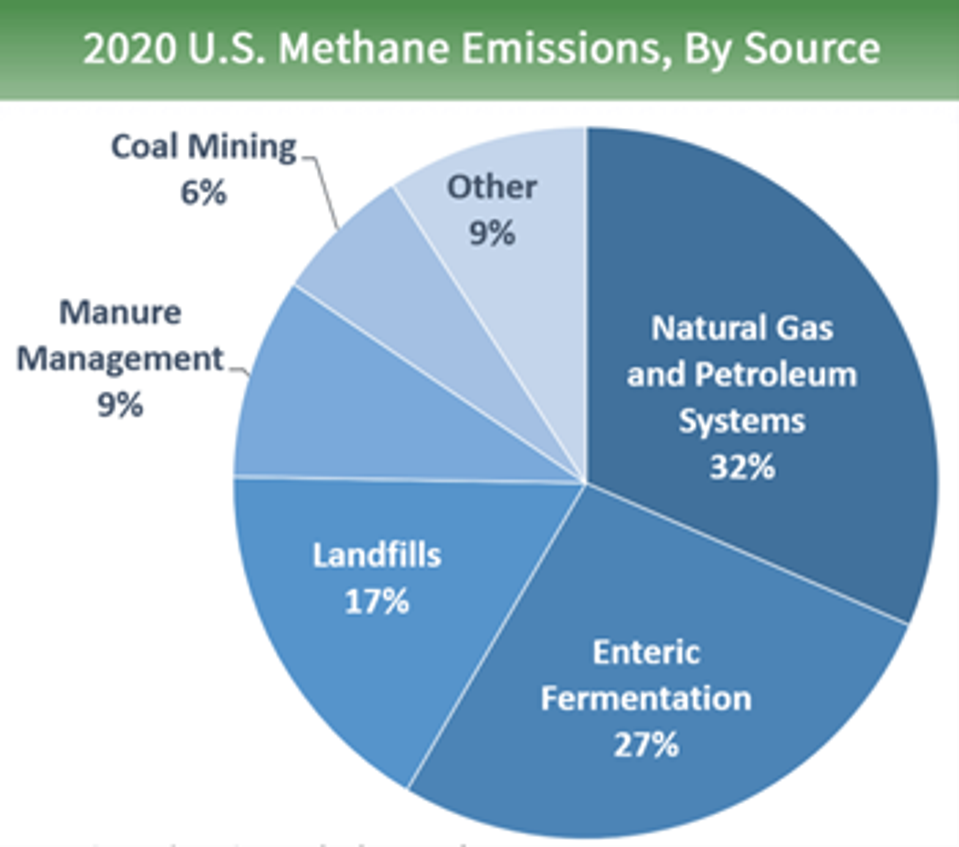

The reason that cows and other ruminants (sheep, goats, deer…) can access the stored energy in cellulose is that in their complex, four-chamber digestive systems there are bacteria that do the work of turning cellulose into its component sugars. That is the upside. The downside is that some of those gut microorganisms generate methane – a “greenhouse gas” with 21 times the global warming impact of carbon dioxide (although with a shorter life in the atmosphere). The cows burp out that gas and this “enteric methane” is estimated to account for about 30% of all global methane emissions. According to the EPA, methane represents 11% of the total US greenhouse gas emissions in CO2 equivalents, and 27% of that is from these animal sources.

Sources of methane emissions for the US

It is often said that consumers should simply eat less beef and dairy-based foods as a climate-conscious response, but that “solution” does not address the cellulose-based energy access question or alter the fact that these are nutritious and appealing foods.

The good news is that multiple strategies are being investigated that could significantly reduce the amount of methane that each cow generates. One of these strategies involves a feed additive called 3-NOP that was developed by the Dutch company, DSM. When 3-NOP is included in the cow’s diet it’s methane production is reduced by 22-35%. The technology is already on the market in Europe under the name Bovaer® and it is also in use in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Australia and Thailand. In April of 2022 DSM and the US animal health company Elanco announced a strategic alliance to commercialize this product in the US. Unfortunately the technology could face a significant delay getting to U.S. farmers and ranchers because while in other countries 3-NOP has been regulated as a feed additive, in the US it may be regulated as a veterinary drug. That is a much slower path that could have the US lagging behind the rest of the world when it comes to this significant opportunity for climate change mitigation.

The countries that have approved this product have considered it to be a feed additive, not a drug. Dr. Frank Mitloehner is an animal scientist at the University of California that has studied this and other methane mitigation strategies. He considers the classification of 3-NOP as a drug to be inappropriate. 3-NOP better fits the definition of a food as it provides nutritive benefit or energy to the animal.

There is political support for an updated approach to the regulation of feed additives with an environmental benefit and claim. The current secretary of Agriculture, Tom Vilsack, has encouraged the FDA to modernize its approach to the classification of feed ingredients to facilitate reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, and that opinion is supported by Dan Glickman, the secretary of Agriculture under President Clinton. In its 2022 fiscal appropriations bill, Congress directed the FDA to study its old policy and make the appropriate changes.

Headquarters of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

On October 18th of this year, the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine held a listening session that included this topic. Louise Calderwood the director of regulatory affairs for The American Feed Industry Association provided a detailed recommendation for why the FDA should “follow the science” on this topic. As she put it, “we believe our country does not have time to waste. Our farmers and ranchers are prepared to do their part, and it is time for the Food and Drug Administration to recalibrate the clock and move ahead with long needed changes to its policy.” She made it clear that “the AFIA is not asking the FDA to create a new regulatory pathway.”

In a positive scenario FDA would classify 3-NOP as a food, the best fit regulatory pathway. Classifying 3-NOP as a food provides a safe and reasonable approach to getting this tool into the hands of farmers sooner, allowing agriculture to have a faster positive impact on climate. The net effect, is providing solutions to climate change challenges in a more timely fashion and the U.S. leading the way, not playing catch up.