One century after starting its first distillery, Japanese drinks titan aims to keep family control, find new ways to achieve goals.

The family that controls Japan’s Suntory Holdings moves at its own pace and focuses on the long term. It goes with the territory. After all, its marquee product and biggest money-spinner are award-winning, world-famous whiskies, which can take decades to age.

The private company, which this year marks a century of whisky-making, had ¥2.7 trillion ($19 billion) in revenue in 2022. It has held its own in Japan’s fragmented spirits, beer and soft drink markets and taken major risks as it ventured overseas. Its $16 billion deal in 2014 to buy listed U.S. bourbon distiller Beam (maker of the iconic bestselling brand Jim Beam), one of the largest international acquisitions by a Japanese corporation, catapulted Suntory into the big leagues. Today, Suntory remains the No. 3 spirits maker globally by revenue after U.K.’s Diageo and France’s Pernod Ricard, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

Over the past decade, Suntory’s Japan whisky sales have doubled to ¥195 billion, according to the company. Domestically last year, Suntory had over half the whisky market by volume and is the No. 3 brewer, with 16% of volume, after Asahi (34%) and Kirin (29%), says data provider Euromonitor International.

Fewer Cheers

Alcohol consumption in Japan has declined over the past 15 years. But whisky has held its own, rising nearly all years since a decades-long nadir in 2007.

Still, Suntory faces twins challenges in its domestic market of a rapidly graying and shrinking population and the trend of imbibing less. In the past three decades, the per-capita consumption of alcohol, including beer, sake and spirits, has dropped by one-quarter, according to the National Tax Agency, to 75 liters annually. Key factors are more people concerned about their health and fewer younger people drinking.

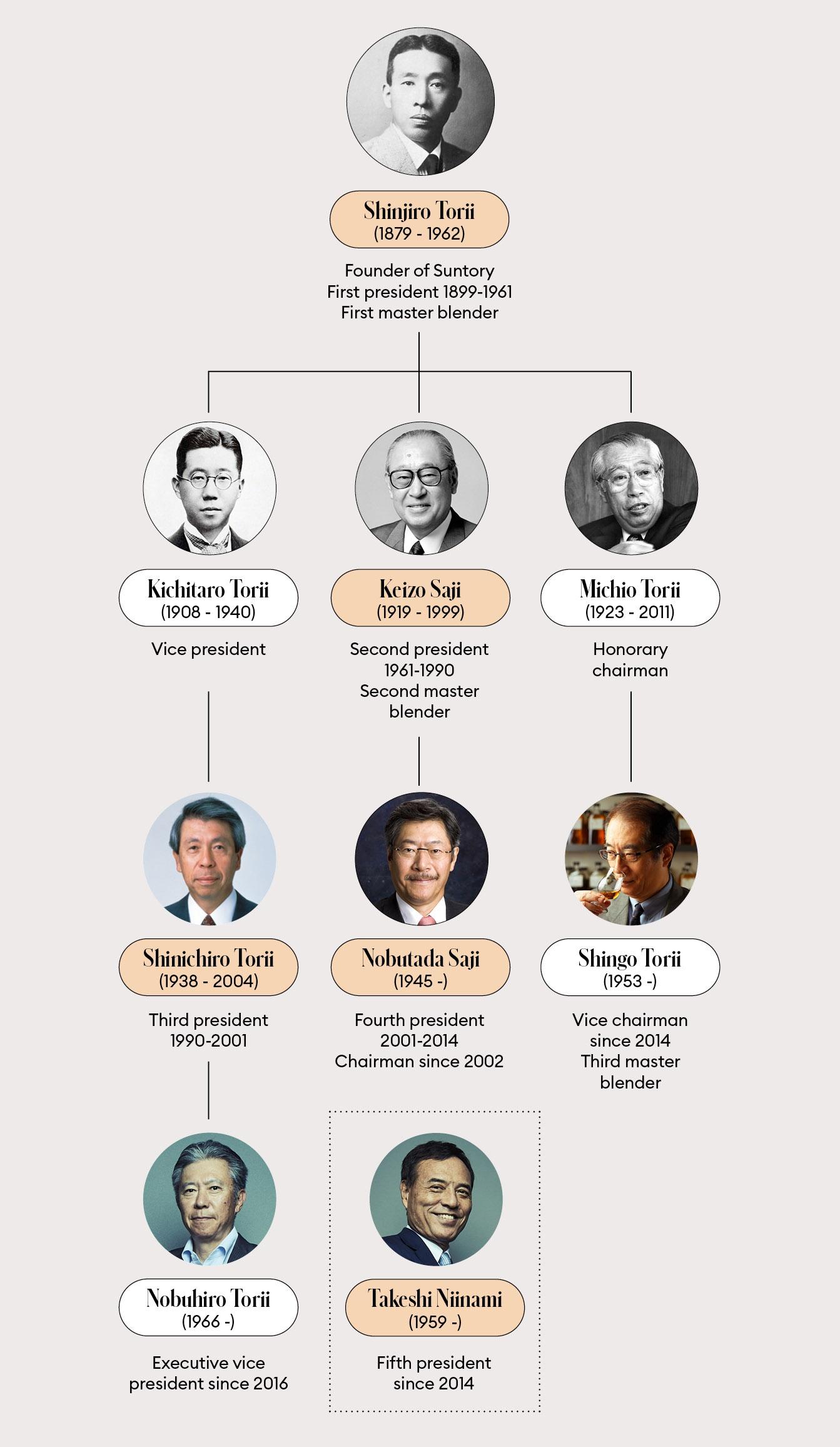

And looming for Suntory is a long-anticipated change of leadership, back to a member of the founding family. Since 2014, the CEO and president has been Takeshi Niinami, the former head of a major Japanese retailer and the first non-family head of Suntory since its founding in 1899. For years, there have been signs that the next in line to lead the company will be executive vice president and chief operating officer Nobuhiro Torii, nephew of 77-year-old chairman Nobutada Saji and great-grandson of Suntory founder Shinjiro Torii (descendants use both Torii and Saji surnames). Saji, who doesn’t have any children and declined to be interviewed, has an estimated personal net worth of $1.2 billion.

Separate interviews with Niinami and Torii did not bring much new detail on the timing of a change at the top. Niinami, 64, says how long he remains CEO is “up to Saji-san and the founding family members.” Torii, meanwhile, made some general comments on what he wants to do when he becomes CEO.

Torii, 57, does note there needs to be more change to put the company where it wants to be. “We can’t achieve our goals based on the incumbent ways of doing business,” he says. “We need to be more innovative, with out-of-the-box thinking.” There were no specifics on broad goals, other than his focus on whisky and health and wellness. Suntory has a target of ¥3 trillion in revenue in 2030, excluding alcohol taxes, says Niinami, a target that’s 11% above last year’s figure.

Maciej Kucia (AVGVST) for Forbes Asia

One thing that is ahead is more globalization. In the decade through 2022, Suntory has diversified out of Japan to double its overseas sales, bringing it to over half of revenue, and increased the percentage of alcohol revenue to 35% from 28%. Next up the company is eyeing an additional investment into tequila—it already has five tequila brands under its Beam Suntory division. It is also open to further expansion in India through an acquisition. “Tequila is global,” says Niinami. “We’d like to acquire a tequila brand or maybe scotch or others to change our portfolio from those that we now have … in soft drinks, we want to go to some other countries where we don’t have any footprint. Same as in spirits. In India, we might acquire local ones. If there are some good candidates, I think anytime we’d want to make that happen.”

Saji has been nurturing Torii, much like aging a whisky, for decades for the top job, assigning him increasingly important roles. At times, the chairman has publicly been tough on his nephew. “Nobuhiro is working hard. But he’s still young and needs to show more results. So, we may need a pinch hitter,” Saji told a Japanese weekly magazine in a rare interview in January 2013.

Just over a year later, Saji announced that interregnum. After a five-year courtship, Niinami agreed to leave his role as chief executive of Lawson, one of Japan’s largest convenience-store operators, and join Suntory to lead the Beam integration and expand its international business. Fluent in English and armed with a Harvard M.B.A., Niinami had quickly advanced at Japanese trading giant Mitsubishi Corp., after joining it in 1981. Niinami says the Beam integration was a merger of cultures as it was of operations. “It took them a long time to understand who we are—the value of the Suntory spirit, the value of what we are trying to do,” he says.

President and CEO Takeshi Niinami has led Suntory since 2014.

Maciej Kucia (AVGVST) for Forbes Asia

Niinami discussed his likely successor, unusual in a country where companies almost never telegraph top personnel moves. “Nobuhiro faces a really challenging time now. While shouldering a critical role at Suntory, he is also president of Kotobuki Realty and preparing to take on the mantle of the next generation [of leadership],” Niinami said in an interview for journalist Hidekazu Izumi’s 2022 book Heredity and Management: Nobutada Saji’s Convictions. Kotobuki, the private Osaka-based asset manager owned by the Torii and Saji families, in turn controls Suntory Holdings.

Like his uncle Saji and Niinami, Torii graduated from one of the top finishing schools for Japan Inc.’s chief executives, Keio University. He also earned a master’s degree in international economics and finance from Boston’s Brandeis University in 1991. He spent six years at the Industrial Bank of Japan, now part of Mizuho Financial Group, before joining Suntory in 1997.

One of Torii’s first major Suntory roles was leading the premium beer business from 2006. While its rival Tokyo-based Sapporo Holdings pioneered that market with the Ebisu brand in the 1990s, Torii dethroned it as the sales leader in 2008 with Suntory’s Premium Malt’s brand. Suntory, which entered the brewing business in 1963, finally turned a profit on beer in 2008 when it overtook Sapporo as the No. 3 brewer by overall volume. The following year, Torii led the deal to acquire France’s Orangina Schweppes and, as CEO of Suntory Beverage & Food in 2013, oversaw its listing on the Tokyo stock market, the only part of Suntory that is a public company.

Satoru Abe, a former Suntory executive, who worked with Torii and spent nearly four decades at the firm, says Torii leveraged his financial knowledge while leading Suntory’s search for acquisition targets. He notes Torii led three major takeovers (Orangina, New Zealand’s Frucor and the U.K.’s Lucozade and Ribena brands), including their post-merger integration. “With expectations for over ten years that he would be the successor, he has worked to build up his experience and knowledge,” Abe says by email.

Suntory Holdings’ executive vice president and chief operating officer Nobuhiro Torii, great-grandson of Suntory founder Shinjiro Torii.

Maciej Kucia (AVGVST) for Forbes Asia

From the interviews, it’s clear that one thing not on the agenda is having the holding company go public. The CEO and the COO rule the idea out. Soft-spoken Torii, a contrast to the gregarious Niinami, becomes more animated when discussing why Suntory Holdings ought to remain private. “There are only three reasons to be listed. Capital is needed. People are needed. Or honor is needed. In today’s Suntory, while we have debt, we don’t really need more capital. Attracting people, not an issue. The need for honor, including profits to the founding family, not an issue either. That’s why we don’t need to list,” he says.

Japan has over 25,000 firms that are a century or older—with over 90% of them family run, indicating a durability not seen elsewhere, says Toshio Goto, chairman of the Tokyo-based 100-Year Family Business Research Institute. But there’s a history of families losing control because of dilution of stakes, internecine struggles or mismanagement.

To Goto, there are three key characteristics of companies lasting 100 or more years: A business that is sustainable over the long term; strong family governance and internal communication; and maintaining strong communication between the family and non-family staff. The Saji and Torii families meet all these metrics, says Goto, who has been researching family-run businesses for over two decades. Suntory, which has maintained its independence and corporate culture, has a hybrid private and public structure, where unlisted Suntory Holdings holds a nearly 60% stake in listed Suntory Beverage.

“As companies get larger and larger, the family influence usually gets smaller and smaller. That’s a pretty iron-clad, historical rule that is pretty hard to change. Despite that [Suntory has] continued,” he says. “That’s a very successful example. That company has continued for over 120 years and become an enormous one too.”

Torii says no further dilution of the stakes among family members would be ideal, but that it will occur naturally as shares are inherited by another generation. “When the time comes, we will have to seriously think about what to do. Taxes will change, and we’ll have to think about how to deal with that. Right now there are shares with voting rights and those without voting rights, so we’ll have to think about various options,” he says.

Suntory Musashino Brewery in Tokyo.

Courtesy of Suntory

For most of its existence, Suntory, founded in 1899 as wine importer Torii Shoten, was led by the family—for three straight generations through Saji—and mainly expanded organically. Growth was first with wine and whisky and later beer and soft drinks. But there were acquisitions in this century, like Beam, on Saji’s watch as CEO. (A 2009 agreement to join with Tokyo-based rival Kirin Holdings fell through the next year after differences over a merger ratio that would have valued Suntory too cheaply, Saji says in Izumi’s book.)

Strong returns may be key for the family maintaining control, as it would help keep Kotobuki’s shareholders from being enticed by any potential buyout deal. While Niinami, who spoke in English during the interview, says that on an operating-profit margin basis, Suntory is targeting 15%, which he described as the “global standard,” both he and Torii note the diverse nature of Suntory’s portfolio, with high margin whisky and lower margin soft drinks.

When Torii was Suntory Beverage’s president from 2011 to 2016, and regularly met investors in the U.S., he was constantly asked about low margins. Though Torii laments the difficulty in raising prices because of the nation’s decades-long deflationary environment, he says the ability to do that appears to be emerging as consumers become more accustomed to price increases. “What I can say is that the margins in Japan are too low,” he remarks.

Niinami’s mission is to internationalize Suntory further to make it a “truly global company.”

Although the pandemic hit Suntory Beverage’s operating income in 2020, that figure has rebounded sharply in 2021 and 2022, surpassing 2019’s pre-pandemic number of ¥114 billion, on ¥1.3 trillion in revenue.

Daiwa Securities forecasts that the firm, which is only one of two that it has a buy rating on among the two dozen firms in Japan it covers in the alcohol, soft drinks and food sector, will see operating profit jump 25% to ¥142 billion this year from 2019, and to ¥159 billion in 2024. That metric for domestic rivals such as Kirin and Asahi Group Holdings is expected to rise at a much slower rate or drop this year and the next, Daiwa says. “In addition to being able to make appropriate price increases, it has been able to increase market share,” Daiwa analyst Makoto Morita wrote in May of Suntory Beverage. “Even during the coronavirus pandemic, it has continued to invest in its brands and sales and marketing efforts, and that’s why I think it has been able to expand its share.”

Another important development for Suntory Beverage was the appointment in March of Makiko Ono as CEO, which, according to Suntory, makes her the first female chief executive of a Japanese firm with a ¥1 trillion-plus market cap.

Suntory Holdings has “well-established” market positions in both alcohol and non-alcoholic beverage sectors in Japan, a diversified portfolio with strong brands, and an improving geographic diversity, Moody’s wrote in a June report. But Suntory’s profit margins lag those of global alcohol firms because of lower soft-drink margins diluting overall margins, it said.

Torii says two of his longer-term goals are to expand the health and wellness business, which remains a small part of Suntory Holding’s revenue and includes health drinks, food and supplements, and to make Suntory’s whisky the world’s bestselling brand. “Whether it’s products, some value-added services or—not sure if we can do it, something like a subscription service model, health and wellness is a wide area [to build upon],” he says.

As for Niinami, he says he wants to finish the job of globalizing Suntory and that he will stay on in management in some form, even if not in the CEO role. Indicating a broadening of his focus, in April, he became the chief of the Japan Association of Corporate Executives, the Keizai Doyukai, one of the nation’s three main business lobbies.

In Izumi’s book, Saji is quoted as saying “Of course, it depends on what Niinami wants to do, but I would really appreciate it if he could look after Nobuhiro and help him mature as an executive … The journey doesn’t end because Nobuhiro has become president. Even once president, growth will still have to continue and having Niinami’s international prowess would be reassuring.”

Niinami says his mission is to internationalize Suntory further to make it a “truly global company.” Acquisitions will happen but not a major deal like Beam. “I’d like to leave it to the next generation,” he says.

All in the Family

From 1899 until 2014, Suntory has been headed by a member of the Torii and Saji families, both related to the founder. When the tenure of Niinami ends, the founder’s great-grandson, Nobuhiro Torii, is seen as heir apparent to take the reins.

Source: Suntory.

Photos courtesy of Suntory; Michio Torii by Getty Images; Nobuhiro Torii & Takeshi Niinami by Maciej Kucia (AVGVST)

Distilling Demand

Shinji Fukuyo, Suntory chief blender.

Courtesy of Suntory

Suntory’s most recognized products are its whisky brands, especially its Yamazaki label. This year Suntory is celebrating a century since it began building its first distillery, in Yamazaki near Kyoto. The firm took the lead in putting Japanese whisky on the global map and nurtured—then rekindled—Japan’s affinity for it.

So ingrained is whisky in the company’s DNA that its master blender, Suntory’s top whisky expert, has been a family member from the beginning. The first was founder Shinjiro Torii, and today it is his 70-year-old grandson, Suntory vice chairman Shingo Torii. “He’s thinking about the direction of the whisky business while, as master blender, he’s looking at the flavors and smallest details of distillation,” says Suntory chief blender Shinji Fukuyo, who works under Torii. (Torii was unavailable for comment).

Along the way, there were tough times. At some points during a quarter-century slump that ended in 2007, only one of the Yamazaki Distillery’s six pairs of pot stills operated. But the company continued to invest and to develop new blends, says 62-year-old Fukuyo. In 2007, whisky volumes plunged to one-fifth their 1983 peak, according to Japanese tax agency data. As an unlisted company, however, Suntory Holdings could focus on the long term.

Limited edition bottles of Hakushu and Yamazaki whisky to mark Suntory’s 100th anniversary of whisky-making this year.

Courtesy of House of Suntory

Today, sales are booming, and Suntory continues to win international accolades for its aged Yamazaki and Hakushu single malts and Hibiki blends, with some bottlings auctioned off for hundreds of thousands of dollars. A combination of current high demand and, during the doldrums, lower production and pricier aged whisky sold in cheaper blends, have contributed to the present shortage.

During the slump, “we had to make sales plans on how to use the whisky stocks. It was tragic because it was a continued decline,” Fukuyo says in an interview at the distillery. Starting in 2008, Sun-tory revived the moribund domestic market through a campaign to promote whisky and soda highballs in bars (and with retailers the following year). “It went from a period where, if going out to dinner, we wouldn’t see a single soul drinking whisky to one where everybody was drinking it. And you’d see characters on TV shows drinking whisky highballs,” he says. “I was quite flabbergasted.”

In February, Suntory announced a ¥10 billion investment to renovate the Yamazaki and Hakushu Distilleries and plans for a rarer, more costly way to process barley, called floor malting—done by hand rather than by machine—a sign also of Suntory’s continued quest to improve the quality of its quaff.

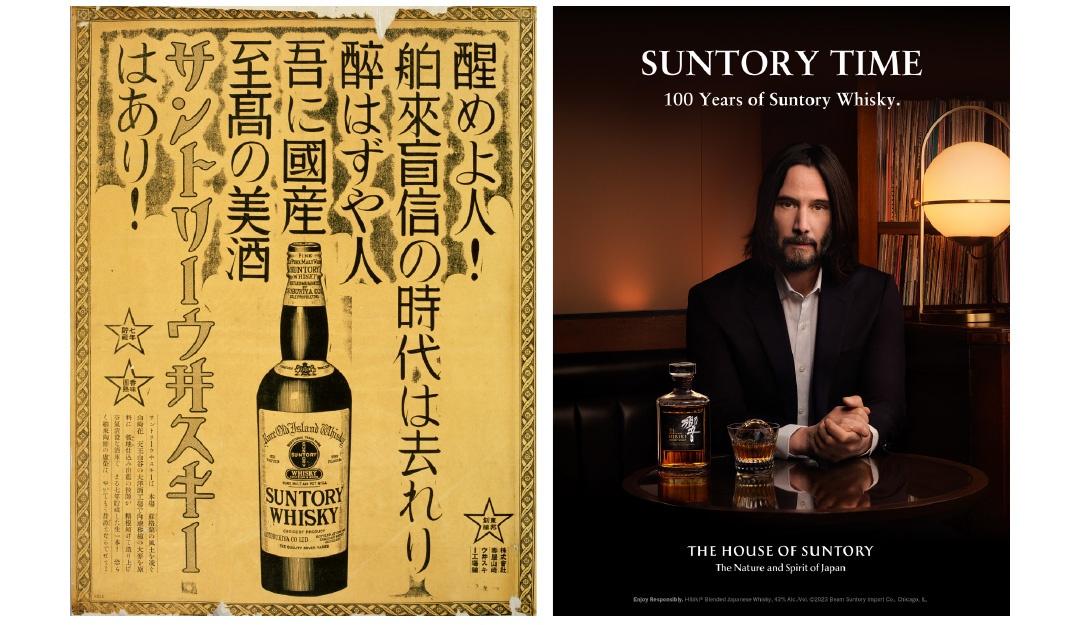

Advertisement for Suntory whisky in 1929 (left), Japan’s first authentic whisky. Suntory whisky’s centennial advertisement in 2023 featuring Keanu Reeves.

Courtesy of Suntory

Brand Building

Some of Suntory’s advertising and marketing campaigns have been legendary. One of its most memorable came in 1922, thanks to an advertising poster of famous Japanese actress Emiko Matsushima holding a glass of the company’s Akadama Port wine. Her shoulders and upper torso are unclothed, while the rest of her figure hidden in shadows. Though tame by today’s standards, the image was controversial in its time for its alleged “nudity”—and made Akadama Port a hit. The profits from that campaign helped fund the building of the Yamazaki Distillery, and Akadama Port is still sold today. The symbol for that fortified sweet wine was the sun and later became the basis for the portmanteau of Suntory—“sun” plus the “Torii” surname—when the company officially changed its name to Suntory in 1963.

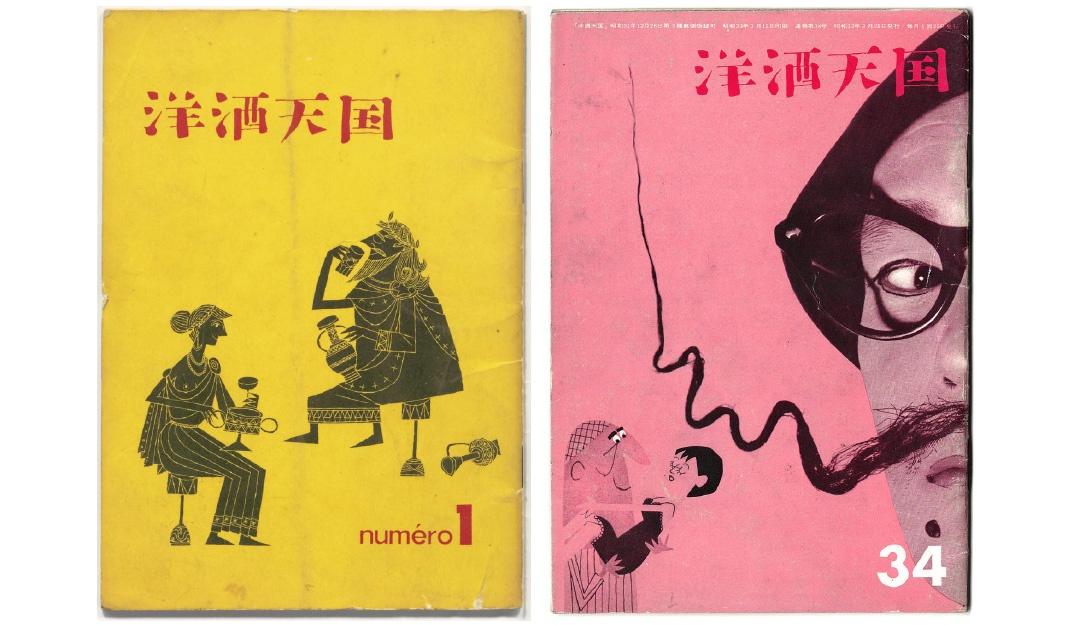

In the late 1950s through the 1980s, Keizo Saji (president 1961-1990), who traveled in artistic circles, wrote essays and composed poetry, tapped literary and marketing talent, including two who eventually won top Japanese literary prizes, for ad copy, commercials and a free magazine, Yoshu Tengoku (Western Spirits Heaven), akin to the U.S men’s publication Esquire. About 240,000 copies, at the peak, were distributed to some 2,000 Torys bars that Suntory operated mainly in the 1950s and 1960s. That and other campaigns, coupled with double-digit economic growth, ginned up interest in whiskey, helping to ignite and maintain its postwar sales boom. In 2008, Suntory replicated that feat by reviving domestic whisky sales from a decades-long slump with another marketing campaign.

First and 34th editions of Yoshu Tengoku, the creation of Suntory’s legendary advertising and marketing department. It was a free magazine published in the late 1950s through the early 1960s.

Courtesy of Suntory, James Simms

Suntory’s Story

Suntory has a long history of making spirits and supporting endeavors aimed at benefiting society. Here are some milestones of the company’s business development and philanthropic activities:

1899 – Shinjiro Torii (1879-1962) founds Torii Shoten in Osaka and begins to produce and sell wine.

1907 – Releases Akadama Port Wine, renamed Akadama Sweet Wine in 1973.

1921 – Creates Kotobukiya Limited to own the business; starts Hojukai Social Welfare Association in Osaka, first as free medical clinic, later providing child and elderly care.

1923 – Begins construction of Yamazaki Distillery near Kyoto.

1929 – Releases Japan’s first authentic whisky, Suntory Whisky Shirofuda (White Label).

1937 – Launches Suntory whisky Kakubin (square bottle).

1946 – Starts Suntory Foundation for Life Sciences in Kyoto to promote bioorganic chemistry and related research.

1950 – Opens Hibarigaoka Gakuen Elementary School near Osaka, later adds secondary schooling.

1961 – Inaugurates Suntory Museum of Art in Tokyo.

1963 – Enters beer market with Suntory Beer; Kotobukiya becomes Suntory Limited.

1972 – Opens Chita Distillery for grain whisky near Nagoya.

1973 – At newly opened Hakushu Distillery near Japan’s Southern Alps, Suntory sets up “Save the Birds” sanctuary.

1979 – Establishes Suntory Foundation, which has a 9.2% stake in family asset manager Kotobuki Realty, owner of private Suntory Holdings, to support scholarship, arts and culture.

1983 – Acquires Bordeaux winery Château Lagrange.

1984 – Releases Yamazaki’s first pure malt whisky.

1986 – Opens Suntory Hall in Tokyo. Conducting legend Herbert von Karajan calls it a “jewel box of sound.”

1989 – Introduces Hibiki malt and grain whisky.

1994 – Unveils Hakushu single malt whisky.

1996 – Releases Sesamin E health supplement.

2003 – Launches Natural Water Sanctuary Project, now in 22 areas, to enable replenishment of underground water resources; Yamazaki 12 Years wins Gold at 2003 International Spirits Challenge.

2005 – The Premium Malt’s beer, first released in 2003, wins Japan’s first Grand Gold Medal in Monde Selection beer category.

2007 – Opens new Suntory Museum of Art in Tokyo.

2008 – Buys New Zealand’s Frucor Group for €600 million.

2009 — Acquires France’s Orangina Schweppes Group for about ¥300 billion; establishes Suntory Foundation for the Arts, which holds a 13.8% stake in Kotobuki, owner of unlisted Suntory Holdings.

2009 – Announces plans for Suntory Holdings and Kirin Holdings to merge.

2010 – Scraps merger with Kirin, due to differences over the merger ratio.

2013 – Acquires U.K. soft-drink brands Lucozade, Ribena for £1.35 billion.

2013 – Lists Suntory Beverage & Food on the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

2014 – Purchases U.S. bourbon distiller Beam in $16 billion deal.

2021 – Starts initiative in Scotland to restore and conserve peatlands and watersheds.